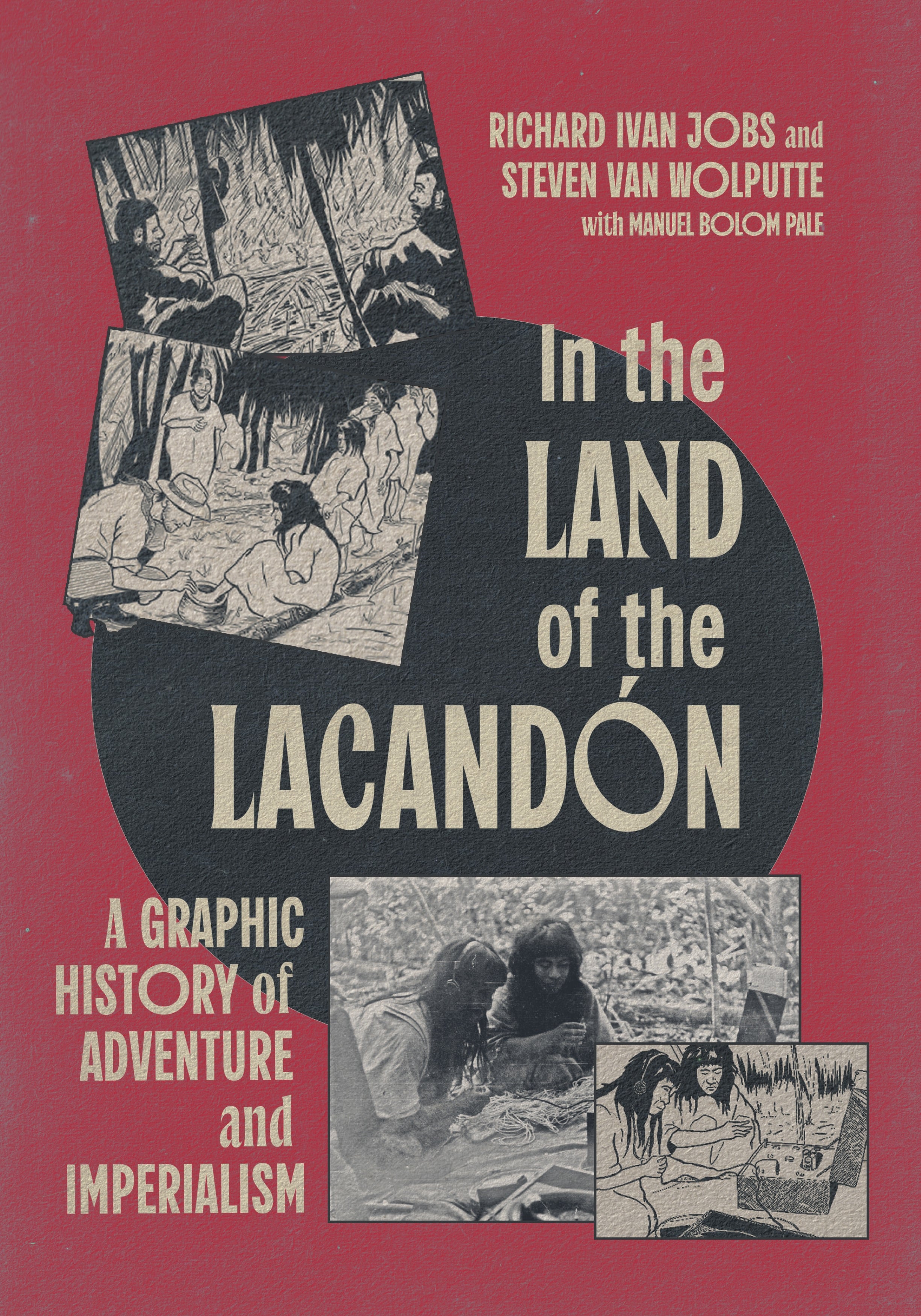

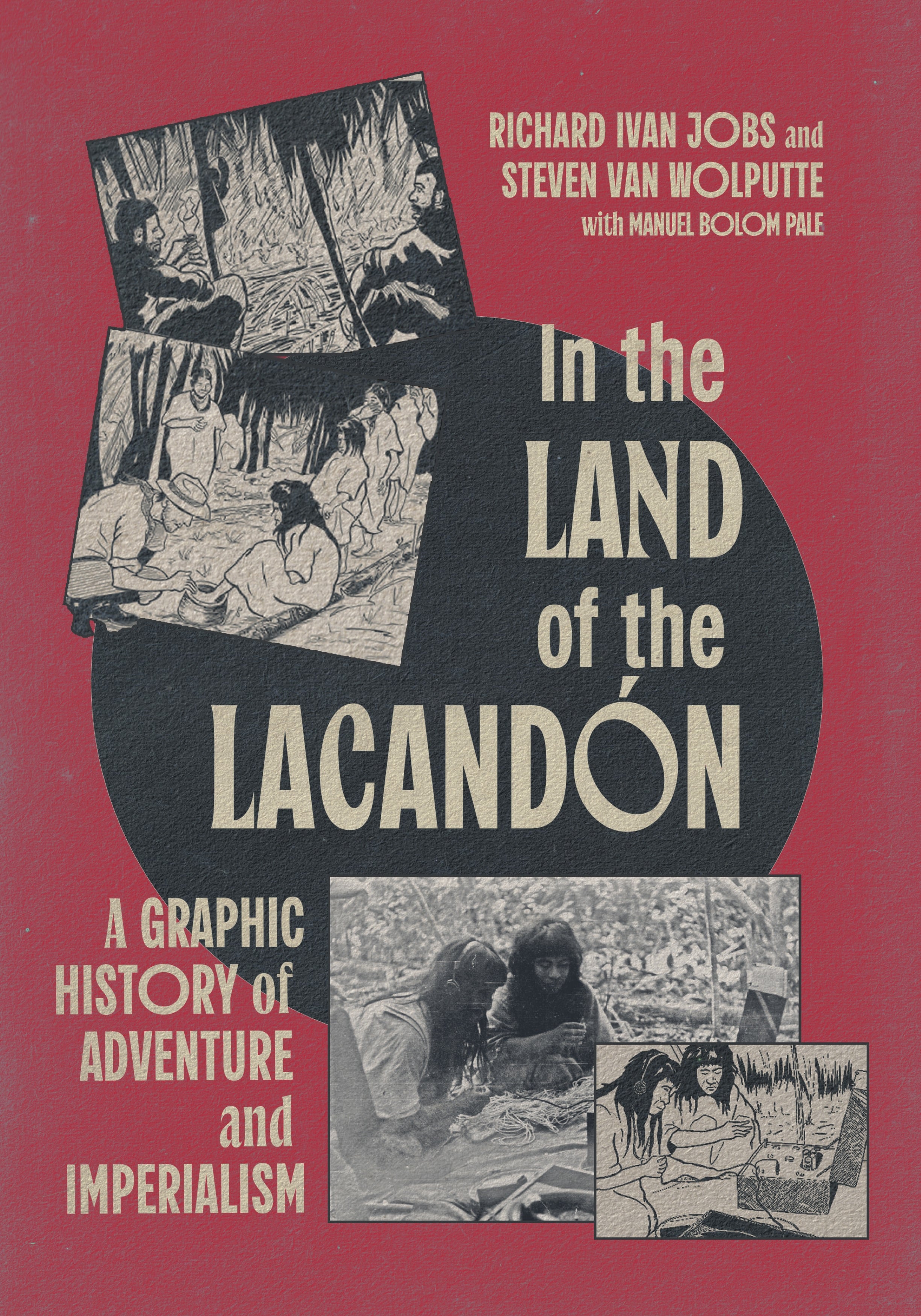

McGill-Queen’s College Press launched In the Land of the Lacandón: A Graphic Historical past of Journey and Imperialism, written by Richard Ivan Jobs and illustrated by Steven Van Wolputte, earlier this month.

Within the Land of the Lacandón follows Bernard de Colmont, a French ethnographer and beginner filmmaker who ventured into Chiapas within the mid-Nineteen Thirties to review the Lacandón folks and broadcast their lifestyle to a curious European public. The Lacandón, thought-about a “misplaced tribe,” have been thought-about the closest dwelling kinfolk of the traditional Maya. Whereas de Colmont’s adventures generated quite a lot of consideration, the Lacandón have been silenced in his story.

A century later, Richard Ivan Jobs and Steven Van Wolputte created a graphic historical past primarily based on de Colmont’s narratives and pictures. That is offered alongside an essay contextualizing the story and an evocative, reflective poem by Tsotsil author Manuel Bolom Pale, providing an Indigenous perspective on the encounter.

The Beat talked to Richard Ivan Jobs about Within the Land of the Lacandón, how tales of the colonial-imperialist hero seem in media right now, and the historical past of exploration, science, and media.

OLLIE KAPLAN: Within the “Preface,” it’s acknowledged {that a} graphic historical past format was chosen as a result of it allowed the workforce to create “a single complete narrative” out of “a mash-up of assorted scattered and incomplete authentic sources. Are you able to elaborate on why you needed to inform this story as a graphic historical past?

RICHARD IVAN JOBS: We had dozens of authentic images and a documentary movie to make use of as visible sources. Furthermore, we had radio lecture transcripts and journal articles authored by Bernard de Colmont himself. Thus, slightly unusually for a graphic historical past, we didn’t should depend on inventing photos or fictive narration to inform the story, however might draw immediately from major historic sources. As for the story itself, the primary time I got here throughout it, with out having completed any of the analysis, I noticed it as an journey comedian e-book. I had simply completed a slightly bold scholarly monograph and was trying to do one thing artistic, suave, and enjoyable with historic storytelling whereas nonetheless adhering to historic strategies.

KAPLAN: How does Within the Land of the Lacandón study imperialist narratives? What parallels do you see between the Nineteenth-century imperialist gaze and up to date cultural or tutorial encounters with Indigenous communities?

RIJ: We attempt to attract consideration to imperialist narratives by telling an imperialist narrative that’s self-aware. So a lot of our up to date concepts about race, civilization, hierarchy, modernity, and so forth have their roots in tales informed about European imperialism’s encounter with Indigenous peoples. These concepts stay enduring and embedded in our tradition right now, however there’s additionally a unprecedented critique of them. One want solely take into account the latest outstanding commentary on empire by Andor, for instance.

KAPLAN: Who’s Manuel Bolom Pale? What was his position within the mission?

RIJ: Manuel Bolom Pale is a prize-winning artistic author from Chiapas. He’s an Indigenous Maya and infrequently writes in Tsotsil, his Indigenous language. Our e-book riffs a bit on who will get to talk, who will get to inform tales, and who will get to make histories, so we requested him to jot down one thing artistic for the e-book to assist draw consideration to those themes. His poem, printed in Tsotsil and English, evokes a particular worldview from the Lacandón informed via a number of views.

KAPLAN: Are you able to stroll me via your collaborative course of with Steven Van Wolputte?

RIJ: Steven received concerned very early on. I had positioned the periodicals, movie, images, and radio lectures which have been the bottom materials for the comedian. So he received began fascinated by that bit whereas I continued doing analysis, studying, and writing. Largely over e-mail and sometimes on Zoom, we’d commerce concepts, swap drafts, give suggestions, and so forth, all through. It is very important level out that Steven is an anthropologist who attracts. So, intellectually, we understood one another very nicely in recognizing and creating themes and fascinated by how we would combine these visually into the comedian, and likewise what factors we wanted to develop within the essay.

KAPLAN: How did you choose a visible fashion paying homage to mid-century European comics?

RIJ: My very first scholarly journal article was about comics censorship laws in postwar France. So I’m fairly aware of interwar and mid-century comics, francophone and in any other case. Steven is Belgian with a deep information of comics/BD. From the outset, I envisioned this story as a Nineteen Thirties Tarzan or Tintin or the like. Our graphic evokes the fashion of that period and makes use of the format as each homage and critique.

KAPLAN: Star Trek is quoted early on, drawing an instantaneous parallel to fan criticism that TOS has an American imperialist bent. How is Gene Roddenberry’s idea of a “Wagon Practice to the Stars” paying homage to the colonial hero-explorer narrative?

RIJ: Captain Prepare dinner/Captain Kirk. The Endeavor/The Enterprise. Each are ships filled with scientists on voyages of discovery whereas doing the work of colonization and empire. That temporary reference attracts consideration to how generally imperial narratives are embedded in popular culture, which is one other of the themes we tackle.

KAPLAN: What sources or archives have been most instrumental in creating this narrative? How would a lay individual method doing the sort of historic analysis?

RIJ: That’s powerful. Most of the supplies I discovered have been scattered round archives and libraries in three nations; for instance, the radio transcripts that proved particularly precious have been in a folder in a field in a small archive in Paris. Nonetheless, huge numbers of newspapers and magazines have been digitized and can be found and searchable via varied interfaces. Typically you must apply for entry, at different instances there are charges. However that’s one thing one can do from wherever with good web and relentless key phrase looking. Additionally, I need to observe that quite a lot of historic analysis is secondary: that’s, we learn the work of different historians–you be taught heaps, perceive your supplies higher, they usually lead you to different major sources. Learn books everyone!

KAPLAN: The graphic novel attracts consideration to imperialist narratives of authenticity and the hurt they trigger. Why is it precious to look at historical past from numerous views?

RIJ: Historical past itself is human-made. It’s an evidentiary research and interpretation of the previous, which signifies that folks have created historic narratives specific to particular worldviews. We fairly explicitly needed the reader to consider the historical past of information manufacturing: anthropological, scientific, historic. The broadening of whose histories are studied and whose tales are informed helps to grasp the previous extra expansively and extra deeply for all of us.

KAPLAN: What’s subsequent—do you intend to pursue extra graphic histories, or was this a one-time mission?

RIJ: I actually don’t know. For the primary time in thirty years, I’m not engaged on something. Steven and I had a beautiful time engaged on this. I’m certain if considered one of us comes up with an thought, the opposite can be eager. As a result of I don’t draw, I’ll want a collaborator!

KAPLAN: Is there the rest that you just need to add?

RIJ: We expect we’ve completed one thing distinctive by making use of various literary varieties to inform this historical past: graphic, essay, poetry, and dialogue. We hope readers discover it entertaining and illuminating.

Within the Land of the Lacandón: A Graphic Historical past of Journey and Imperialism is now accessible from McGill-Queen’s College Press.